A scientist with heart and soul

We could imagine nothing pleasanter than to spend all of our lives digging for relics of the past.

Heinrich Schliemann

He started to learn about the secrets of the universe along with learning the

alphabet, and astronomy became his lifelong hobby, but not his profession. He

devoted many years to meteor astronomy, nowadays he prefers flyovers of artificial

satellites. He observes, records and analyzes with the same precision artifacts

from the Stone Age as well as the movement of spacecraft around the Earth.

Patient, persevering and keen observer, scientist with heart and soul.

Marco Langbroek.

The town of Leiden is a place where the oldest university in the Netherland is

situated. Many renowned physicists, including Nobel laureates worked at the

university and for a certain period Albert Einstein gave lectures there too.

Leiden is also your birthplace and hometown. Although you graduated here, your

subject had nothing to do with natural sciences. What is your profession, your

day time job?

I am an archaeologist, specializing in the Palaeolithic: the archaeology of our earliest ancestors. Think Neandertals, handaxes, that kind of stuff. I got my MA and PhD in Leiden, have worked as a field archaeologist for two municipal archaeological services and now work as a post-doc researcher at the VU University in Amsterdam.

The former home of Ehrenfest where Einstein used to stay, a large now somewhat

dilapidated white house is not far from my home by the way, and so is the old

Observatory of Leiden. The latter is some 300 meters from my home.

As an archaeologist you are digging for relics of the past, but early in your

childhood you turned your searching look at the opposite direction, to the sky.

How did you discover astronomy?

My interest in astronomy started around 1976, when I was 6 years old. I had seen

broadcasts about the Viking landers on Mars, and then my parents bought a book

about the planets. It interested me, and when my parents noticed the interest

was staying, they made me a member of the Dutch Youth Association for Astronomy

(JWG) late 1978. In 1979, when I was 9, I built my first telescope, a 6 cm

refractor with a good achromatic lens and rainpipe tube under the guidance of

people of that club.

You were a passionate stargazer in your youth. Have you ever thought to be a

professional astronomer?

I always wanted to study astronomy, but I never was very good in mathematics,

so by the end of highschool I had to let go of that idea. I have always been

interested in history as well, so considered history as a study. Archaeology

sounded slightly more adventurous. So I choose archaeology and got my MA in

1998 and PhD in 2003.

Astronomy became one of my hobbies. The funny thing is of

course, that I would end up doing more or less both: astronomy and archaeology,

the one as a semi-professional amateur, the other as a professional. To my

archaeological colleagues, it is still very confusing when they discover that

I also have peer-reviewed astronomical publications on my name!

What were your favourite targets in the sky?

For several years I focussed on planets and deep-sky, first with the 6 cm, later

with a 4" Newtonian I bought from money I saved from the money my parents gave

me to buy schoollunches. I was quite active in the Youth Astronomy Association

at that time, became part of the editorial staff of its magazine 'Universum'.

At the age of 19 I was asked to fill a monthly column about deep-sky observing

with small instruments in Zenit, the largest Dutch astronomy magazine. I wrote

that column for several years. About the same time, my focus started to shift

however, to small objects in the solar system: comets, and meteors.

In the 1980´s there was an absence of big comets, none of them were bright enough,

and the return of "the old lady" 1P/ Halley was nothing extraordinary. Which

comets did you observe?

1P/Halley was my first comet, and I next observed some not too bright comets like

one of the Bradfield comets in '87 and a few others in the magnitude +4 to +7

range that appeared in the second half of the eighties. The absence of bright

objects untill Hyakutake and Hale-Bopp came along in the nineties was why I left

the field of comets again and switched to meteors. I actually searched for new

comets with my 4" Newton, visually, in the evening twilight sky for two years but

never found one.

You became a keen and very busy observer of shooting stars ...

From the nineties onwards, I completely turned to meteor astronomy. As a member

of the Dutch Meteor Society, I took part in large observing expeditions that

covered the Leonid outbursts of the nineties and early 2000's. It took us all

over the globe: Spain (1995, 1999, 2002), France (1996), Portugal (2000), the

USA (2001), and of course the Mother of all Expeditions: Northwest China in 1998,

a cooperation with the Chinese Academy of Sciences and NASA. That was very special:

observing the 1998 fireball outburst at -23 C and 3.5 km altitude from a remote

high desert on the edge of the Tibet-Qinghai plateau.

What did awake your interest in meteors?

In 1989, on an open day at the Leiden Observatory where the local chapter of our

Youth Astronomical Association volunteered, I met Peter Jenniskens. He has

played a major role in how my career as a high-level astronomy amateur took shape.

At that time he was a PhD in astronomy in Leiden and starting up his work in

meteor astronomy. He was my mentor in meteor work, and guided me into semi-professional

observing activities. As a result, I now have authored or co-authored several

peer-reviewed papers on meteor astronomy. Peter left the Netherlands in 1992

for NASA's Ames Research Center and subsequently became a well-known meteor

astronomer.

He is the person who organized the big NASA Airborne Campaigns with aircraft

with equipment during the Leonid meteor storms, and who organized the expedition

that recovered the first fragments of the 2008 TC3 asteroid impact in Sudan.

I owe much of what I have accomplished as a high-level amateur astronomer to him.

The meteor work had some spin-offs, partly because I have a very broad interest

which often makes me explore new issues. I started collecting meteorites (and

now have a nice collection of these, plus impact glasses and impact crater breccia),

and my interest in meteoric fireballs led to spin-off interests in asteroids

and satellite decays.

Meteor observation requires a lot of time, which is limited only to night hours.

How could you share your time for study and meteor observations, especially

during your expeditions around the world?

In my twenties I was a good multi-tasker. And when I was doing my PhD, I planned

my hollidays to coincide with major meteor campaigns.

Around 2004, I became very ill. Doing big meteor campaigns became too stressful.

Later, after I recovered from my illness, my work started to take more and more

of my energy too. So I turned to the much less tiring and time-consuming (but fun!)

business of satellite observations around 2005. In fact, almost all of my current

observing activities concerns satellites: I am part of a small international

(and rather informal) network of observers that do position determinations, and

from that orbit determinations, of classified satellites. These observations are

done from my home in the Leiden town center, mostly using a DSLR camera, a suite

of lenses, and astrometric software that was originally developed to measure

multistation meteor images.

It was also the time when you started your participation on pro-am asteroid

collaboration ...

My work with asteroids indeed started around the same time. In 2004, a fellow

amateur (Jeff Brower) introduced me to the Spacewatch FMO project that used

volunteers to review photographic plates taken at Steward Observatory on Kitt

Peak for Fast Moving Objects (FMO): Near Earth Asteroids! It meant that over

many 2004-2006 mornings, I started the day by starting up my computer, logging

in, and inspecting several images taken the previous hours with the 0.9 m

Spacewatch telescope. I inspected over 3000 images before, on 2005 April 9,

this led to my discovery of the Amor asteroid 2005 GG81

You were not only one of the most persistent volunteer but also administrator of

the FMO mailing list. How could someone became such an administrator?

Stu Megan had set it up, but at a certain moment decided to stop. I then offered

to take up the effort and constructed a new mailing list, as I felt the social

contacts among the FMO people which the mailing list and forum enabled, were a

very good thing.

Another field where you participated very intensely was asteroid searches in the

SkyMorph archive. How did you get knowledge of it?

Partaking in the same FMO project, and soon in the social network that sprang

from it, Rob Matson was the person who introduced it to others. He is the second

person, after Peter Jenniskens, who has been very important to me in introducing

me to and guiding me into a particular field of semi-professional astronomy. Rob

learned me how to extract images from the Skymorph archive, work with Astrometrica

to measure them, and use Findorb to chase the new objects we discovered in the

archive, leading to more images on more nights, and eventually to designations

issued by the Minor Planet Center (MPC).

What was the reason for starting your hunt?

Reasons were that it is fun to do, and it helped me fill cloudy evenings and

rainy Sundays. When satellites remained hidden behind clouds, the internet NEAT

archives at Skymorph became my hunting ground... I have a scientific mindset.

Obtaining new knowledge and 'discovery' has always been the bread and butter of

my life: it is why I became a scientist. It is part of my profession, and part

of my hobbies. I explore, observe, record, investigate, analyse...: whether it

are stone tools, geologic outcrops, asteroids, meteor activity, satellites,

dragonfly species around a pond....that really is me. Curiosity, and an urge to

explore new frontiers. There is still so much to discover on this world, and

in our skies!

There is another possibility to make discoveries using internet, similar to FMO

Spacewatch project - searching for SOHO comets. This challenge did not attract

you at all?

No, and I can't quite explain why. Somehow, it isn't that attractive to me.

Maybe because it lacks the astrometry and recovery through orbit fitting

procedures (it is merely detecting something on a SOHO image and reporting it).

You discovered 57 minor planets in the NEAT archive, many of them now got a

permanent number and even several were named. What is your most highly esteemed

result from the SkyMorph hunt?

The three Jovian Trojan asteroids I discovered are special (2001 SD355; 2002 WV27;

2002 WG29). It makes me feel like I am modestly following in the footsteps of the

famous Van Houtens, the Dutch astronomer couple working at Leiden Observatory

who during the sixties and seventies discovered most of the Jovian Trojans, using

the same Palomar telescope that NEAT employs. My most special discovery is however

not from Skymorph/NEAT, but from the FMO project: 2005 GG81. I never forget the

morning I saw that little trail pop up on the image, and got the message back

from Spacewatch that it had been submitted to the NEOCP (Near Earth Object

Confirmation Page).

Later, when you mastered how to search for unknown asteroids you wrote a "Guide"

which was very helpful to other hunters, including myself. After you were guided

by Rob Matson, later you passed it on others. Was it a satisfaction for you when

asteroid (183294) got the name "Langbroek" in your honour?

I felt very honoured by it. And it is good to hear that the guide I wrote has

been of use to others. It means it served its purpose!

Although you started your asteroid hunt in the time when the MPC did no longer

credit discoverers itself (as it was earlier), but the NEAT programme, you could

name 7 of your discoveries. How did you feel when you proposed those names to

the MPC?

I felt privileged that I could honour several deserving people in this way. The

names I proposed so far, concern either long-active, high-level amateur astronomers

from the field of meteors, asteroids and satellites, or some of my professional

"heroes" from palaeoanthropology (Eugene Dubois and Lewis Binford). It feels very

good to be able to honour people you admire for their contributions in this way.

You traveled almost all over the globe to watch meteor showers, is there still a

place on Earth which you would like to observe the sky from?

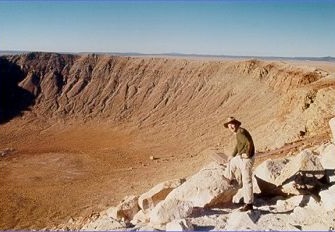

I have been privileged to observe from many places on this planet: in the remote

Qinghai province of China; the Arizona desert; Senegal; the mountains of Spain

(even on Calar Alto in 1995) and Switzerland; the countryside of France, Spain,

Portugal, Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands. I would like to observe the

southern meteor showers and the Magellanic Clouds once from Australia. That is

one thing on my 'to do' list.

What is your favourite astronomy book?

A special one to me will always be Carl Sagan's "Cosmos", derived from the TV-series

of the same name. I watched the TV series as a boy in the early eighties, and

it heightened my already awakened fascination with astronomy even more.

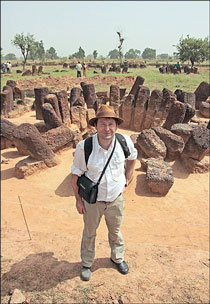

In contrast to many archaeoastronomy "specialists" and certainly fringe people a

lá Erich von Däniken, you are a real expert in both, quite different sciences,

in archaeology and astronomy. What do you think about archaeoastronomical theories?

I must say that in most cases I am very critical of archaeoastronomical studies,

especially those done by astronomers rather than archaeologists. Many of those

studies go over the top, over-interpret chance alignments and ignore the wider

archaeological context. They also frequently try to picture prehistoric humans

as "scientists", as observational astronomers, and put much too much emphasis on

"calendar functions" etcetera.

But I believe many allignments on midwinter suns etc. were never made to be

actually observed: they were created for the symbolism of it (much like the

buried Viking ships in ship burials were never made to actually sail in).

And prehistoric humans really didn't need a stone sightline to determine it was

time to start plowing and sowing rye or einkorn: they would know that from other,

environmental clues. Meticulous time-keeping and observations on meridian transits

are merely obsessions of our modern time, where meticulous time-keeping is

important while at the same time we have lost, in our western urban society at

least, contact with the significance of signs like returning birds and the blossom

date of flowers.

What does astronomy mean to you?

It is a part of my life and lifeworld that will always be there. Nothing reliefs

stress more than lying on your back under a dark star-spangled sky, watching

shooting stars and the milky way. I can't resist looking up whenever the sky is

clear.

Every Schliemann searches for his Troy. Is that of yours still hidden beneath the

soil or revolving somewhere in the of deep space?

Who knows? The interesting thing about both astronomy and archaeology is that you

cannot properly predict what you will find. So who knows what is in store? Only

time will tell!

Instead of an epilogue

In 2009 you stopped searching the NEAT archive after finding 57 asteroids. Then 3 years passed and

you started a new search, this time real time images from observatory Piskésztető in Hungary.

How did this happen?

In the summer of 2012 I joined the Piszkéstető (Konkoly, HU) asteroid survey of Dr. Krisztián Sárneczky

as a volunteer plate reviewer, looking by visual inspection of the images for objects that have been

missed by the automated plate inspection routines. The survey makes use of the Konkoly Mountain Station

(Hungary) 60 cm Schmidt telescope. This work is usually done in the evening hours. My first discoveries

in this survey were done during the October 2012 run. In February 2015, I discovered a NEA as part of

this survey: 2015 CA40.

The year of 2012 was full of exciting activities and unexpected events for you. In November,

out of the blue, you were awarded by the Royal Dutch Astronomy Association. What was that?

It was the annual Dr J. van der Bilt prize for my work on meteors, asteroids and meteorites. With

the prize money, I bought a Celestron C6.

Instead of finding out what performance can offer your new telescope you started work on the Diepenveen meteorite.

Tell us about it.

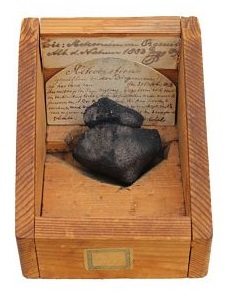

Yes, that year I got also the opportunity to get involved into the research of a new and intriguing meteorite,

the Diepenveen carbonaceous chondrite. Eventually, this would lead to a research job at the Dutch National

Museum of Natural History from 2015 to 2017.

The story of that meteorite is decidedly unusual. It fell in October 1873, so 146 years ago now, but its existence

was completely unknown to science until 2012.

The meteorite fell in an agricultural field near the hamlet of Diepenveen in the east of the Netherlands. The fall

and impact was witnessed by field labourer Albert Bos and his wife, who picked it up and brought it to the village

teacher. The 68 grams stone ended up at the Higher Civilian School (HBS) of nearby Deventer town, where it entered

into a curiosa collection, that was soon completely forgotten. It probably spent the better part of a century gathering

dust in the attic of the school.

When the school was closed down almost 50 years ago, a teacher 'rescued' some stuff from the inventory that was

being thrown away: including a small wooden box with this meteorite in it. It sat decoratively on his fireplace

for many years, until he passed away. His widow then gave it to a friend of the family, Mrs Kiers, who collected

stones. She had it for years, not realising how special it was. Then serendipity played the joker in the summer

of 2012: as it happens, Mrs Kiers visits the same camping during summer holliday each year, and her neighbour on

that camping is Henk Nieuwenhuis, the retired curator of the historic Eise Eisinga Planetary in Franeker. When

Mrs Kiers organised an ad hoc exhibit of her stone collection, as part of some summer activities for the local

community, Henk spotted the box with the stone, and realised what it was. He contacted Niek de Kort, the then

president of the Royal Dutch Association for Astronomy, who agreed it looked genuine, and both of them next

contacted me.

I nearly got a heartattack when I got the pictures: not only was it clearly a genuine meteorite, but I immediately

recognized it as a rare carbonacous chondrite, meteorites that contain carbon compounds, sometimes including Amino Acids.

I started up research and classification of the Diepenveen, not realizing at that time that that research eventually

would grow very big, six years later resulting in a 31-page paper in Meteoritics & Planetary Science with me as main

author and 25 co-authors from 20 different international research institutions.

It landed me a temporary research position at Naturalis Biodiversity Center (the Dutch National Museum of Natural

History) in my hometown Leiden in 2015 and again in 2017. I am currently still a guest researcher at the museum.

So suddenly I found myself doing professional meteorite research, and working at a National Museum!

It turns out Diepenveen is a regolith breccia, a unique case, even among the already rare CM Chondrites.

Interestingly enough, the reflection spectrum of Diepenveen is similar to that

of asteroid Ryuku: the asteroid currently visited by the Hayabusa2 sample return mission. So, I am very

curious to see how the Ryugu samples compare to Diepenveen when the spacecraft resturns the samples in

December 2020.

In 2017, another new Dutch meteorite fall happened, at Broek in Waterland just a few km north of Amsterdam.

This was a fall which occurred in very early evening twilight of 11 january 2017. Two-and-a-half weeks later

Niek de Kort was contacted by a young couple that said that on the morning of 12 January (the day after the

fall), they had noted damaged roofing tiles at their garden shed, and found a blackened stone lodged in the

roof of the shed. We went to Broek in Waterland to investigate, on behalf of the museum. It was a 0.53 kg L6

chondrite, the sixth meteorite of my small country.

As you mentioned, since 2005 you have been tracking spy satellites, capturing their positions

and then determining orbits, which for obvious reasons are not made public. In 2014, great plane

accident shook the world. You were asked for help in connection with the investigation.

What was it about?

The catalyst was something horrible and dramatic: the shootdown of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over

the Ukraine on 17 July 2014. As we now know this civilian airliner was shot down by a Russian BUK

anti-aircraft missile, perhaps misidentifying it as a Ukrainian military aircraft. Of the 298 passengers

and crew that sadly lost their lives that day, 193 were fellow Dutch (and for me personally, it came

uncomfortable close because I would have flown the same route with the same airline only 3 days later).

I wrote a blogpost on my satellite blog (sattrackcam.blogspot.com) discussing which US infra-red early

warning satellites might have observed the missile firing. That was picked up by a Dutch Parliament member,

Pieter Omtzigt, who in January 2016 organized a hearing on MH17 of the Permanent Foreign Affairs Comittee

of Dutch Parliament, in which a number of relevant experts were heard by members of Dutch Parliament:

law experts, radar experts, Dutch Intelligence experts, crash investigators, the president of the European

association of Air Traffic Controlers etcetera. And he invited me as an expert to this hearing too, to brief

the committee on which (military) satellite systems might have observed the missile firing.

Only three days after that hearing, I was contacted by the Dutch Royal Air Force, by their brand new Space

Security Center. They were interested in my expertise with tracking classified satellites. A year later,

this resulted in a job, when I was enrolled as consultant on Space Situational Awareness issues to the

Space Security Center of the Royal Dutch Air Force. Interestingly enough, as the result of taking a broad

definition of "Space Situational Awareness', this project will incorporate Near Earth Asteroids as

well, although only as a 'byproduct' (we will be looking into

spectropolarimetric characterisation).

What are your activities besides strict and accurate science?

As a result of the above events, I started to be active in the media.Over the

past years, I have frequently (and increasingly so) appeared in Dutch and international newspapers,

and frequently on tv programs and in radio programs related to my activities: on topics ranging

from asteroids to meteorites to satellites to North Korean missiles. I have been a guest in several

Dutch prime-time nation-wide television programs, and on US TV in a PBS documentary by Miles O'Brien

on OSINT investigation of North Korean missile launches. I have done radio interviews with Dutch,

British, US and German radio stations the past years.